Weirdcore - Dreamcore - CoreCore

The Ontology of Digital Aesthetics

Have you ever found yourself scrolling through TikTok or Pinterest, and stumbled upon a dreamlike collage of surreal, nostalgic, or unsettling images? Yes. Probably you have. These aren’t random collections; they belong to the internet’s growing lexicon of aesthetic 'cores'—dreamcore, weirdcore, corecore, and more. What are these digital aesthetics? Are they merely echoes of traditional artistic movements, or do they represent something entirely new, born from the unique conditions of the digital age?

In this exploration, I will analyze these aesthetics by examining the broader concepts of digital aesthetics. What does it mean for these "cores" to exist, and how do they reshape our understanding of art, identity, and reality?

Dreamcore

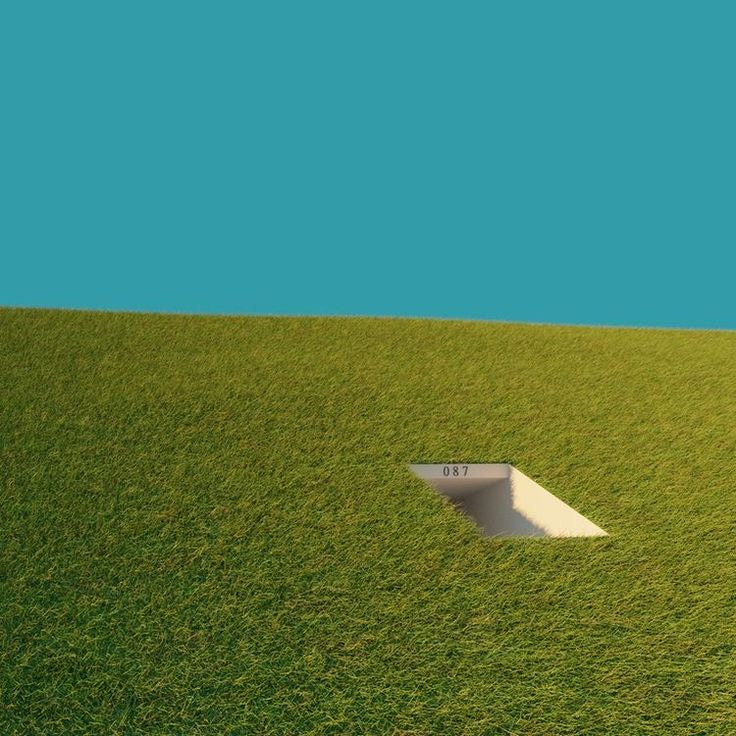

Dreamcore evokes the sensation of stepping into a lucid dream, or a liminal state where the boundaries of reality dissolve. Its surreal, ethereal visuals which often include glowing objects, or relics of childhood like forgotten toys, and liminal spaces, create an atmosphere of nostalgia that is intermingled with the uncanny. These images feel like portals to a dreamscape that feels intimately familiar yet also creepily alien.

Dreamcore extends the principles of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto, which described surrealism as a "pure psychic automatism" that seeks to unite the real and the dreamlike. However, dreamcore transcends surrealism by situating itself in a digital matrix. Whereas surrealism was trying to uncover the unconscious through physical art forms, dreamcore operates as a shared digital dream that is curated collaboratively across platforms. It is the algorithm—not the unconscious mind—that bridges the real and the surreal.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s concept of phenomenology deepens our understanding here: dreamcore constructs an experiential space where digital images create an embodied, emotional resonance. The nostalgic glow of a CRT television in a darkened room, for instance, is not just an image but a sensation—a reconstruction of memory mediated through the screen.

Weirdcore

Weirdcore confronts us with the uncanny by disrupting the familiar through eerie distortions. Its settings, which often includes suburban neighborhoods, pixelated PC screens, and liminal rooms, feel like memories that have been tampered with. The aesthetic uses glitches, unsettling typography, and strange juxtapositions to evoke disorientation and discomfort.

Sigmund Freud’s essay Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny) defines this aesthetic perfectly: the uncanny arises when something familiar becomes disturbingly strange. It thereby exposes the fragility of what we perceive as "normal." Weirdcore manifests this digitally by throwing us into spaces that seem like they belong in a dream yet feel corrupted by their artificiality.

We can also turn to Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject—that which disturbs identity and system. Weirdcore operates as a digital abject that reveals the dissonance between the known and the alien. Its eerie glitches expose the cracks in our digital realities, asking: What happens when the comforting world we create online turns hostile?

Corecore

Corecore, often described as the "aesthetic of aesthetics," is meta by design. It doesn’t adhere to a specific visual motif; instead, it curates fragments of media like movie clips, viral videos, and melancholic soundtracks, to create an emotional collage. The goal is to evoke existential reflection, alienation, and longing.

Jean Baudrillard’s theory of hyperreality provides a lens to interpret corecore. In a hyperreal landscape, representations lose connection to any kind of tangible reality, and become simulations of simulations. Corecore exemplifies this: it amplifies emotional intensity through carefully curated imagery, but these emotions are detached from the source material. The grief or nostalgia we feel while watching corecore edits is not tied to personal experience but to the simulation itself.

As philosopher Mark Fisher noted in Capitalist Realism, contemporary culture often operates on a "nostalgia for lost futures." Corecore reflects this melancholia by weaving together fragments of cultural memory to simulate a longing for something that never truly existed—a collective dream of an imagined past.

The Internet as a Canvas

The internet is not just a medium for these aesthetics—it is actually their canvas. Platforms like TikTok, Pinterest, and Tumblr serve as decentralized galleries where creators remix imagery into fluid visual languages. So, in a way, algorithms become silent collaborators that amplify trends and guide what aesthetics rise to prominence.

And here lies an ontological paradox: if algorithms play a significant role in shaping these cores, are they still human art forms? Or do they represent a hybrid creativity, where human intention and technological process coalesce? Gilles Deleuze’s concept of assemblage can be applied here: digital aesthetics are assemblages of human creativity, algorithmic selection, and participatory remix culture.

Ontology and Digital Identity

Digital aesthetics are not confined to the realm of visual art; they extend into the sphere of identity. To participate in an aesthetic core is to curate a digital persona—profile pictures, wallpapers, and social media posts aligned with its visual language. These personas are more than projections; they are digital selves that interact with and reshape the core itself.

Jean Baudrillard’s simulacra theory resurfaces here. In curating a dreamcore or weirdcore persona, users create representations of self that are increasingly detached from any "real" identity, and exist more and more as hyperreal extensions. This blurring of self and aesthetic raises more questions: Are these personas expressions of individuality, or do they dissolve individuality into the collective aesthetic hive mind?

The Question of Originality

Tracing these aesthetics back to traditional art movements reveals both continuity and divergence. Dreamcore echoes surrealism’s exploration of the unconscious, while weirdcore channels the uncanny. However, their accessibility distinguishes them. Unlike traditional art, which is kind of elitist as it is often confined to galleries and institutions, digital aesthetics are radically decentralized and participatory.

Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction predicted this shift. He argued that the reproducibility of art in modernity dissolves its "aura," and democratizes its consumption. Digital aesthetics extend this logic, by not only reproducing art but also making its creation a collective act. The result is an unprecedented dynamism: a constant evolution driven by community interaction and technological mediation.

Aesthetics in the Digital Age

Ultimately, digital aesthetics like dreamcore, weirdcore, and corecore occupy a unique space at the intersection of art, technology, and identity. They are shaped by the digital infrastructure of algorithms and platforms, yet they also reshape our emotional and cultural landscapes.

These cores are not just reflections of reality; they construct new hyperrealities. They challenge us to rethink traditional notions of originality, authorship, and identity. As Deleuze and Guattari wrote in A Thousand Plateaus:

"A book has neither object nor subject; it is made of variously formed matters, and very different dates and speeds."

Digital aesthetics, like their philosophical insight, defy categorization—they are assemblages of visual languages, emotional experiences, and collective memory.

The Future of Digital Aesthetics

So…as we continue to shape and be shaped by the internet, one thing is certain: these aesthetic cores are only the beginning. They foreshadow a future where art and identity are increasingly fluid, participatory, and algorithmically entangled. In this strange, evolving place, we are left to plague ourselves with a fundamental question: Are these aesthetics reflections of who we are, or are they creating who we will become?

If you make a purchase on Amazon using the links mentioned below, I receive a commission payment via the Amazon Affiliate program:

Bibliography

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism. University of Michigan Press, 1969: https://amzn.to/4h0T8gE

Baudrillard, Jean, Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press, 1994: https://amzn.to/49Z6sQx

Benjamin, Walter, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Schocken Books, 1968: https://amzn.to/3PmFetI

Deleuze, Gilles, and Guattari, Félix, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press, 1987: https://amzn.to/404jyYb

Fisher, Mark, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, 2009: https://amzn.to/403DrhS

Freud, Sigmund, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny). Penguin Books, 2003: https://amzn.to/41TNfOb

Kristeva, Julia, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia University Press, 1982: https://amzn.to/4gCOOo3

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge, 2002: https://amzn.to/40ehga5

genuinely glad i found this post, what a gem!!! thank you for the research on the topic and congrats on such a cohesive argumentation